This article was written by Brianna Goebel and Liza Graves, with Andrea Blackman as the guest editor. It’s impossible to summarize the fight for women’s suffrage into a 1,500-word article (which is our average article length), so this one is a bit longer. To do the subject justice, it requires at least a semester-long course! But, today, sit back with your cup of coffee and give yourself 15 minutes to read through the highlights of the fight to secure the 19th Amendment. We hope this inspires further reading and learning about this important time in American history, one that is celebrating its 100th anniversary this month.

*****

The history of the fight for American women to vote is long, hard, and messy. It’s a part of history that most of us were barely taught in history classes, and when it was taught, it typically skimmed the surface of the exhaustion, sexism, racism, betrayal, and innovative tactics that were involved.

This is a complicated history and one that deserves celebration, but with clear eyes about all that went wrong and for all who fought hard. The true history has even more heroes than most of us know. More drama, more sisterhood, more betrayal.

First, let it sink in that just 100 years ago, women were fighting for their right to vote. While the 15th Amendment, adopted in 1870, states, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” this only applied to men. The right to vote could still be denied to women on the basis of gender.

Let’s also be clear that the 15th Amendment, while at first enfranchised all male citizens, racism persisted, and within a decade, laws were formed to deny Black men the vote. These laws side-skirted skin color as the reason behind the denial, circumventing the amendment. For example, if one’s grandfather had been a slave, that person could be denied the right to vote (this is where the term “grandfather clause” originates). Poll taxes, literacy tests and intimidation tactics were all used to stop Black men from voting. Therefore, in parts of the country, Black men were voting, but a large majority of the Black community lived in the South, and thus a large majority were denied the right to vote even with the 15th Amendment in place.

It’s important to understand the denial of the vote to Black men as we talk about the fight for the 19th Amendment, as the same set of obstacles was being set up for Black women. This understanding led to two different fights within the women’s suffrage movement: the fight for women’s suffrage and the fight for racial justice along with women’s suffrage.

On August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment was ratified, which states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” While this was a major win for women across the United States, the journey to make this change possible was long and challenging. Taking 72 years to come to fruition, countless female activists broke the mold and forever changed the way women are viewed.

It took until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to ensure that laws created to circumvent the 15th and 19th Amendments, to deny Black men and women their constitutional right to vote, could no longer exist.

As we reflect on our nation’s history, we remember these efforts and remind ourselves of the trials many endured to get here, as well as the progress that is yet to be made, as we continue down the path, always striving for improvement, to make “a more perfect union.”

The 19th Amendment Timeline

The Seneca Falls Convention

Our story starts with two key players: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. The two women met in London in 1840 after they were denied entry to an anti-slavery convention, based solely on their sex. The event served as the final straw for both women, and they came together to create our nation’s first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, NY, on July 19 and 20, 1848.

Over two days, nearly 300 people gathered to hear 32-year-old Elizabeth discuss the rights (or lack thereof) of women. It was here that she read aloud her carefully drafted Declaration of Sentiments. The document outlined 19 “abuses and usurpations” endured by women, such as their inability to sign contracts, attend college, or keep their paychecks if they worked outside the home.

Following these injustices, Elizabeth also included 11 “resolutions,” insisting men and women be treated as equals. But it was Elizabeth’s ninth resolution that was by far the most controversial. She called women to “secure themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise,” or in other words, she was demanding the right for women to vote. It was this idea that eventually became the foundation of the women’s suffrage movement.

It’s of note that Frederick Douglass, a former slave, outspoken abolitionist, and proponent of women’s suffrage, was also a speaker at Seneca Falls. He wrote the following passage after attending the convention:

“In respect to political rights, we hold woman to be justly entitled to all we claim for man. We go farther, and express our conviction that all political rights which it is expedient for man to exercise, it is equally so for women. All that distinguishes man as an intelligent and accountable being, is equally true of woman; and if that government is only just which governs by the free consent of the governed, there can be no reason in the world for denying to woman the exercise of the elective franchise, or a hand in making and administering the laws of the land. Our doctrine is, that ‘Right is of no sex.’”

RELATED: She Fights to Ensure Everyone’s Vote Counts

The Civil War

Soon after that first convention, suffragists were hit with their first major challenge: the Civil War. It was also around this time that Susan B. Anthony joined the frontlines of the movement. Women quickly refocused their efforts on the war and those who had been enslaved. Suffragists believed that when the war ended, every eligible American citizen would obtain the right to vote. The desire was universal suffrage.

Despite this brief refocus on equal rights for all, suffragists quickly learned that the sentiment in the country was not universal suffrage. Women and Black men, both having been denied the vote would not be granted the right simultaneously. Allegiances were severed as women were asked to step aside in favor of Black men. Once united, this split caused deep rifts in the suffrage movement. Both Elizabeth Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were outspoken in their desire to see white women vote before Black men. Black women were left with no side that included them. The united front that started in the abolition movement turned into a battle pitting all sides against one another.

Black suffragist Sojourner Truth is quoted, “I feel that I have the right to have just as much as a man. There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and colored women not theirs, the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before.”

The 14th Amendment (1868) is often referenced for its guarantee of citizenship, which would then include former slaves. However, the 14th Amendment also set up the insertion of gender for eligibility to vote. Previously, the denial of women’s suffrage had been on a state level. The 14th Amendment goes on to define voting as open to male citizens of 21 years old. This insertion of gender, for the first time in the Constitution, is what set up the bigger fight to extend voting rights to women.

The 15th Amendment (1870) was passed to ensure that race could not be used to deny voting eligibility set up in the 14th Amendment. It did not protect gender, and this served to be a huge division in the suffrage movement. While Frederick Douglass, who had been fighting for universal suffrage, supported the 15th Amendment as a compromise to ensure Black men could vote, he lived up to his promise to continue to work for women’s suffrage over the following decades and until his death.

“We can see African American women and white women having different views of what motivated them to vote after the Civil War, particularly in the South,” says Andrea Blackman, who serves as the Director of Special Collections for the Nashville Public Library’s Civil Rights Center, Special Collections Center, and the soon-to-open Votes for Women Center. “That question is still being asked today of what is motivating one to go to the ballot, and sometimes those motivations aren’t the same,”

After the passage of the 15th Amendment, mainstream suffragists split into two groups: The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) and the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The AWSA worked toward change within state constitutions, believing voter eligibility would be better determined on a state by state basis. Others followed suit of NWSA formed by Elizabeth Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, believing the voting rights of women was a national issue. It wasn’t until 1890 that the two organizations joined together again as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and combined both techniques, believing a federal amendment could be passed through state campaigns.

A Standstill

Despite the two sides coming together again, society’s views toward women did not change. At the time, women were viewed as too emotional to have a say in political affairs. Their only concerns were to be related to the home and maintaining its upkeep. Suffragists knew before they could make any change, they had to alter this image of women.

“The 19th Amendment didn’t solve anything as far as what society says are women’s roles — domestically, publicly, in power,” explains Rebecca Price, founder and president of Chick History, a non-profit that works to rebuild women’s history and bring light to key moments. “They were facing the same things that we are. Whenever you have a voice and you stand up and speak out, that’s going to be a challenge. You’re going to have to overcome that, and [suffragists] certainly faced those challenges.”

Despite the creation of NAWSA and this new focus on how women were viewed, the suffragist movement gained popularity in only a few areas of the United States. Western parts of the country were still new and their populations were scarce, so women’s votes were seen as essential. Wyoming was the first state to completely enfranchise women. Over the next six years, other western states such as Colorado, Idaho and Utah followed suit.

Despite this small victory out west, progress within the movement slowed down once again, as there was still the issue of race. As mentioned, many Southern states passed grandfather clauses and laws that required voters to pay poll taxes or take literacy and constitutional tests before casting a ballot. White men sidestepped these laws as they were written to exempt them, excluding those who had a relative who was eligible to vote before 1866 or 1867.

With these racist laws in place, white women suffragists took note. Susan B. Anthony watched these events unfold and the mission of NAWSA was once again altered.

Chapters of the organization began refusing Black members, fearing their presence would defer potential supporters. NAWSA believed if white women were given the right to vote first, they would help enfranchise Black women — which further encouraged discrimination and segregation. By the late 19th century, the organization was primarily made up of white, upper-middle-class women.

“Many African American women supported votes for women and worked for this goal within their own organizations,” says Miranda Fraley-Rhodes, Ph.D., curator of the Tennessee State Museum’s soon-to-open Ratified! Tennessee Women and the Right to Vote exhibit. “However, during this time of segregation, white suffragists often sought to marginalize them within the movement and refused to accept them as full partners.”

Despite this change in membership and mission, the movement proved to be no more effective than before. Between 1896 and 1909, over 160 legislative measures were proposed by suffragists. Women’s suffrage was put to a vote only six times — being defeated each and every time. This period would soon be referred to as “the doldrum,” or depression, of the suffrage movement.

A New Wave of Suffragists

Little did women know, however, there was a new wave of suffragists just over the horizon. Harriot Stanton Blatch (daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton) made history in New York City in 1909. After researching state law and learning it was not illegal for non-voters to be poll watchers, Harriot stepped foot in the voting polls.

Her action proved to be the spark the suffrage movement so desperately needed. At the beginning of the 20th century, women began to work outside of the home, and Harriot wanted to involve them in the suffrage movement. She brought together working-class women and middle-class professionals to create The Equality League of Self-Supporting Women. As a result, the suffrage movement started gaining attention from a broader audience — women who knew how to strike and picket. Before long, women were spending hours on soapboxes, bringing the suffrage movement to the forefront so it would not be forgotten or ignored.

“While these are women who are working 100 years ago, they are doing the tactics that we would recognize today,” says Rebecca. “They are letter writing and protesting. They are politicking with their elected officials. They’re organizing fundraisers. They’re going out and giving lectures.”

In 1910 this hard work paid off as Washington amended its state constitution to grant women the right to vote. As hope was renewed, many women started wearing white and the famous suffrage sashes, while others headed to rallies and parades.

The “First” Protest

Despite this victory, at the end of 1912, 39 states still had not granted women the right to vote. That same year, Alice Paul (another prominent suffragist at the time) was named chairman of NAWSA’s Congressional Committee in Washington D.C. Her first task? To plan one of the first national protests in 19 years.

She organized the protest to take place in the nation’s capital on the night before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Alice knew this would be an event the nation couldn’t ignore. Press from around the U.S., important leaders, and thousands of spectators would be in attendance, giving this event the spotlight it deserved.

Although Alice initially welcomed the inclusion of Black women, there were objections from Western and Southern suffragists. The organizers stopped encouraging Black suffragists from attending and then asked them to march at the back of the parade, including nationally recognized suffragist, journalist and anti-lynching advocate, Ida B. Wells. It is reported that close to 50 Black women did march, some integrated with their professional or state delegations, and some at the back of the parade. Wells ended up joining the Illinois delegation along the parade route while Mary Church Terrell, another well known Black suffragist, marched at the back.

“It can never be stressed enough the amount of segregation that was around that time. We are taught it, we understand that, and we certainly still have our forms of segregation today,” says Rebecca. “[People] were kept in different places either by gender or by race, so this was a physical challenge of how you were going to move about and get to the place you needed to be to get something done. How do you work around that? How do you form your own clubs? How do you form your own initiatives so you can express your political agenda?”

Later that afternoon, when President Woodrow Wilson stepped off his train, he was surprised to see no one in attendance to congratulate him on his recent presidential win. Instead, everyone was watching the parade begin on Pennsylvania Avenue. Nearly 5,000 women were marching down the street behind a float that stated the “great demand.” It read, “We demand an amendment to the Constitution of the United States enfranchising the women of this country.”

The parade went according to plan for about four blocks, but it didn’t take long for the roughly 10,000 spectators (mostly intoxicated men) to intervene. They started to assault marchers, and police officers turned their backs on the uproar. Protesters were forced to march single file down the street, and it was only the arrival of cavalry that put an end to the violence and allowed the protesters to complete their march.

The parade ended up overshadowing the presidential inauguration the following morning, and suffragists realized they had a media frenzy on their hands. The suffragist movement finally received the momentum and attention women were hoping for.

RELATED: What Does This “F” Word Mean To You?

New York’s Vote

New York suffragists — particularly Harriot Stanton Blatch — soon followed in the footsteps of Alice Paul. On February 7, 1915, New Yorkers learned a referendum would be put to vote by the New York electoral college for the first time.

While many suffragists were still focused on a federal amendment, Harriot believed in the power of New York. With a large population and electoral college, Harriot believed if New York passed the amendment, other states would have no choice but to follow. Soon, women in New York started standing in shop windows to give “voiceless speeches,” participating in marches and again doing everything they could to make people pay attention.

On the night of the vote, suffragists were optimistic, believing they had gotten through to their state and its citizens. In the end, the vote lost, serving as yet another blow to the suffrage movement. Other states with large populations soon followed, such as New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. Once again, the movement was at a crossroads as suffragists tried to decide whether they should fight on a state or national level.

The Envoys

Nearly 67 years since the beginning of the fight for women’s rights, four suffragists piled into one vehicle to begin another new wave in the movement. As they headed east to Washington, D.C., from San Francisco, the women planned to stop for rallies, press interviews and receptions across the country.

The trip was again the work of Alice Paul, who now called upon Western enfranchised women for help. She hoped to grab the attention of the Democratic party — who occupied both the presidency and Congress houses at the time. By the time the envoy reached Washington, four Eastern states had voted to keep women disenfranchised, and even President Wilson voiced his concern to a friend, questioning who would take care of the home if women were granted the right to vote.

The Impacts of World War I

Despite another roadblock, the suffrage movement saw an opportunity for advancement when the United States entered World War I in 1917. With Carrie Chapman Catt as the new president of NAWSA, she began working to alter the perception of women. She wanted society to view suffragists as patriotic and hard-working (as many women had to fulfill the jobs of men when they went off to war). To further show her support for the U.S., Carrie sent a letter to President Wilson stating NAWSA and its millions of members would support him in the war.

Throughout 1917, this relationship between Carrie and President Wilson continued as they exchanged over 30 letters. Although the president remained against a federal amendment for many years, he eventually changed his stance, urging the Senate to pass the amendment for women’s suffrage on September 30, 1918.

Once again, however, the amendment failed to pass as many Southern leaders believed it would be the end of white supremacy if Black women received the right to vote. The amendment continued to sit in the Senate as Southern opponents proposed changes to limit voting rights to white women. And at the beginning of 1919, many suffragists were prepared to compromise.

Around the same time, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) applied to be a part of NAWSA. In response, Carrie Chapman Catt asked the organization to withdraw its application to help with the amendment’s passing. The NAACP agreed, but on one condition: that NAWSA pushed for the amendment as it was originally written, without modification. There would be no deal to compromise in favor of the white woman’s vote above others.

A Long-Awaited Victory

On June 14, 1919, the amendment finally passed through a new Republican-controlled Congress with just two votes more than the needed for a two-thirds majority. Suffragists immediately began lobbying for the amendment’s ratification — which required 36 of the 48 states to vote in its favor.

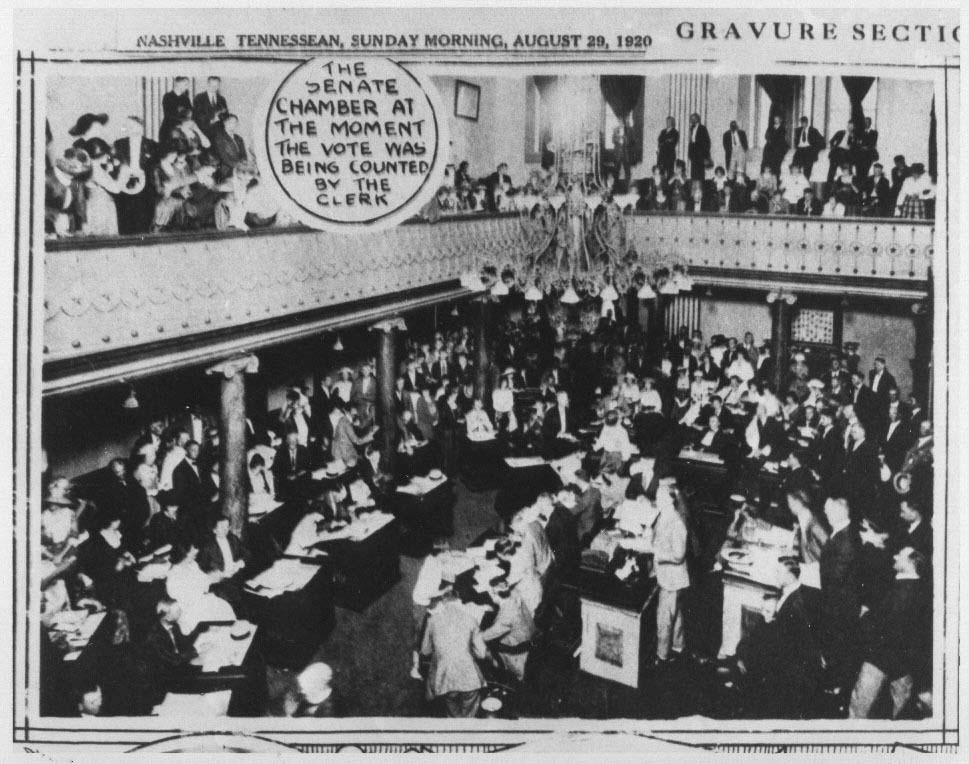

After nearly a year, 35 states had ratified the amendment, leaving only North Carolina and Tennessee to have the final say. In August 1920, suffragists moved to Nashville, TN, to begin lobbying. Staying in the same hotel (the Hermitage Hotel) as anti-suffragists, Carrie Chapman Catt and other suffragists felt a sense of anxiety and dread. Although the vote passed the Senate, it was delayed nine days in the House.

Tallies showed the amendment was unlikely to pass, as suffragists waited anxiously outside of the courtroom. It was 24-year-old Harry Burn who cast the deciding vote thanks to a persuasive letter from his mother.

During the summer of 1920, ratification remained uncertain. Thirty-five states had voted in favor, but one more was needed for the amendment to become law,” says Miranda. “The Tennessee General Assembly provided the critical final approval needed to ratify the 19th Amendment and secure women’s right to vote throughout the nation.”

Nearly 27 million Americans voted in the presidential election of November 1920. Of that, it is estimated that over 8 million women cast their ballot. The battle, however, was far from over. The 19th Amendment, “… expanded voting rights to more people than any other single measure in American history. And yet, the legacy of the Nineteenth Amendment, in the short term and over the next century, turned out to be complicated. It advanced equality between the sexes but left intersecting inequalities of class, race, and ethnicity intact … It helped women, above all white women, find new footings in government agencies, political parties, and elected offices—and, in time, even run for president—and yet left most outside the halls of power. Hardly the end of the struggle for diverse women’s equality, the Nineteenth Amendment became a crucial step, but only a step, in the continuing quest for more representative democracy.” (source) It wasn’t until 45 years later that Black men and women officially found protection for their right to vote through the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which enforced their rights guaranteed by the 14th and 15th Amendments, which also applied to women because of the 19th Amendment.

While we cannot erase our nation’s acts of oppression, we can work to understand a more accurate historical narrative — one that includes women of all backgrounds and races. Today’s article just skims the surface, but hopefully shows that there is much more to history than what we may have been taught. By acknowledging this truth, we can work to create a society where justice and equality are extended to everyone. And, we can more fully appreciate the fight for women’s suffrage and what it set up, what it did not set up, and the political activism sparked that can still be seen today.

The Nashville Public Library’s Votes for Women exhibit opens on August 18, 2020, which is the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment. The virtual grand opening celebration takes place on August 18, 2020, at 11:30 a.m. CST. To learn more, visit library.nashville.org.

If you are intrigued to learn more about the fight for the 19th Amendment, and the political activism that it set in place, we suggest the following articles:

Women Making History, The 19th Amendment (National Park Service, this is the PDF of their official handbook.)

For Black Women, the 19th Amendment Didn’t End Their Fight to Vote (National Geographic)

These 19 Black Women Fought for Voting Rights (USA Today)

**********

For your daily dose of StyleBlueprint sent straight to your inbox every morning, click HERE!