If you’ve ever visited the old Marathon Motor Works building on Clinton Street, it’s a good bet you’ve marveled at the beautiful piece of history that’s retained in the middle of our ever-growing city. Studying it, you can almost imagine its early incarnation as a car factory — the brick walls housing colorful stories of engineering feats and hard labor, and even the Marathon company’s eventual demise. But thankfully, the narrative didn’t die when the factory closed its doors.

We sat down with Owner Barry Walker, who has devoted most of his life to Marathon’s restoration process. Equally notable, he has never wavered from his preservation and documentation of its history. And what a history it is! While some of the initial timeline is fuzzy at best, it’s clear the area now known as Marathon Village has lived through periods of heightened bustle and commerce juxtaposed by some dark stretches of vacancy and neglect. Constructed in 1881 for Nashville Cotton Mills, the buildings were purchased by Marathon Motor Works in 1910 when the company relocated from Jackson, Tennessee.

Marathon Motor Works’ roots originate with an enterprise called Southern Engine and Boiler Works, founded in 1884. A manufacturer of industrial engines and boilers, it easily lent itself to spinning off into an auto manufacturing plant, and so they began working on prototypes in 1906. One particularly ambitious and resourceful engineer named William Henry Collier was instrumental in getting the project out of its design stages, persuading the powers that be to let him build his car and eventually playing a major role in getting it into the hands of consumers in 1907. The company later discovered a conflict with the original car name, Southern, and rebranded the car as Marathon, the first car entirely manufactured in the South. (Rumor has it the name was chosen by a high school student in Jackson, Tennessee — the result of a competition.)

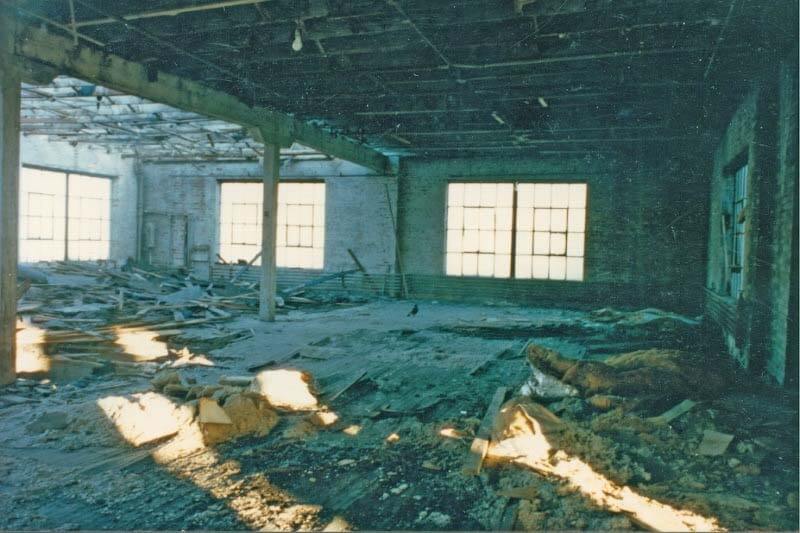

After its relocation to Nashville in 1910, Marathon Motor Works added on to the already existing structure, also erecting an administration building across the street. By 1912, the Marathon company couldn’t keep up with the demand for their cars, and they ultimately concluded production after 1914. The buildings sat empty for a few years until the Werthan Bag Company began using the mill building in 1920, refurbishing it as a bag factory and warehouse. They later moved their business and vacated the premises, and the Marathon framework spent roughly 30 years only vaguely maintained while it remained exposed to the elements and trespassing.

In a sense, it’s Marathon’s current manifestation that ties up some of the loose ends that history left undone. Marathon’s resurrection as a community for artists, retail shops and businesses, with an event space and work studios to boot, has revitalized these centuries-old treasures and given them new life — all thanks to Barry Walker. His acquisition and renovation stories are so wild they might be unbelievable if it weren’t for the well-maintained artifacts and photographs to prove them.

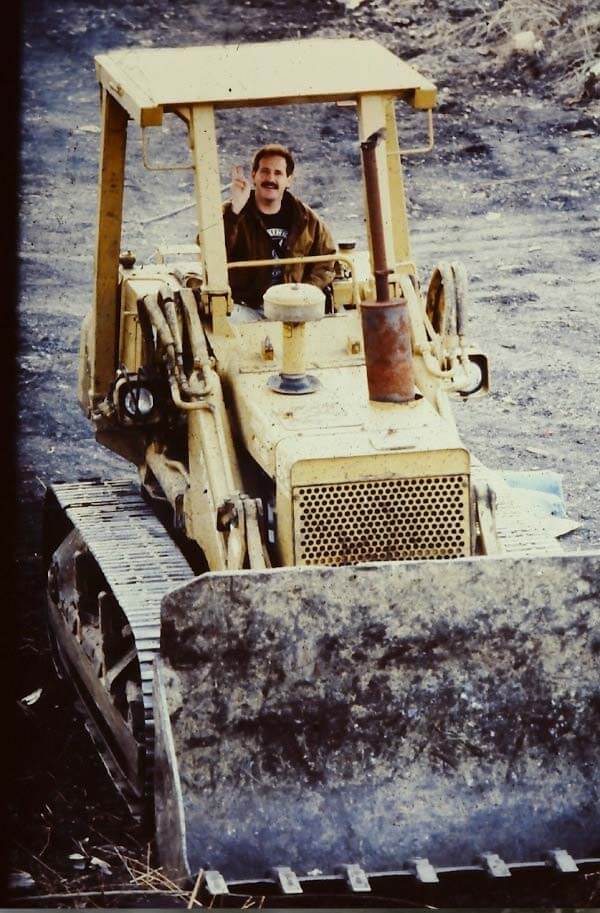

At 23, Barry came to Nashville with only $20 in his pocket. Living on rice and candy bars, and playing music on the side, he held a string of jobs working for local entities like the American Red Cross and the Country Music Hall of Fame. While he may not have finished college, Barry knew he could build nearly anything he put his mind to, so he quit his job to start his own company building anything — from audio-video consoles to elevator rebuilds. He eventually grew out of his basement shop and set out in search of a larger workspace, which is what led him to the Marathon building.

The self-taught builder, designer and entrepreneur ventured into one of the most dangerous parts of Nashville at the time in pursuit of a dream. “By the time I was 29, I had 62 employees, so I needed a bigger shop really bad — that’s what made me drive by here. It was really rough; there were crackheads, prostitutes — but I was desperate, and I saw that the big building was vacant. I drove down the street and people were yelling at me. I saw this massive building with vines all over it. It was trashed, but I was taken by it. So, I drove around on and off for about a year. Finally, in 1986, I decided I was going to try to buy the administrative building. It was cheap because nobody wanted it. Then I restored it and put my shop up here. People laughed at me for years and said I was crazy for doing it.”

The neighborhood was so overrun with drugs and prostitution that Barry’s restoration process included having to take on a more offensive approach to his daily work. “I remember, it was so bad I bought a .38 pistol,” he says. “I’d never had guns like that. And I would come in every day and start shooting into the ground — I would shoot through the door just to scare people off. I would walk in and there would be needles and human feces everywhere; it was disgusting.”

On one occasion, Barry came across a dead body. On another, he witnessed a boy being shot and killed. Most people would have called it quits, but Barry saw through the dust and grime and crime and poverty. “I think a lot of people can’t see through the dirt,” he says. “They go into a space and say, ‘Oh, this thing is nasty, and I can’t breathe; let’s just tear it down.’ Then you clean it out and sandblast it and all of a sudden everyone thinks it’s beautiful. They can’t carry their vision past how gross it is.”

Despite his fear and the filth, Barry was determined to make his dream a reality. He not only recognized the building’s past, but he envisioned its future — one filled with creative professionals and an industrial museum. So, he did what he had to do to overcome the adversity. “There was a guy who threatened me for about three weeks, saying that it was his corner, and he was going to kill me,” Barry recalls. “What helped me get through the early days was ‘Uncle Jack Daniel’s.’ That’s the truth — I did a lot of crazy stuff. This guy kept threatening me and I was scared, so one day I took that .38, and I ran up to him and stuck that gun down his throat. He took off and I never saw him again. I hate to say I did that, but that’s what I had to do. I thought, if I act crazier than they are, then they’ll leave me alone. And it worked; the people in the neighborhood, they were scared to death of me.”

Barry started his overhaul on the administrative building first. “I thought it would take me my whole life,” he admits, “but I got in here in 1986, and I had my first tenants in ’89. By 1992, I bought the back of the factory, and then, by ’93, I bought the entire factory.” And he did all of it without the help of partners or investors. He began renovations in the back and worked his way toward the front, eventually buying up the rest of the neighborhood as well, and officially dubbing it Marathon Village in 1994. By 1996, he had close to 50 companies leasing space between the factory and offices, with retail to follow later.

A pioneer, Barry was the first to ever embark on a major urban renewal project in Nashville by 30 years. Now, it’s all the rage. “I took this over when downtown was still dead,” he says. “When I bought this building, I said, ‘I’ve got all this extra room; I could fix it up and rent it out to artists and funky, creative people.’ And that’s what I did. Back then, nobody had that kind of stuff in Nashville. So everybody wanted in here. They wanted the big windows, the exposed brick … So I filled up pretty fast, even in the ghetto. Then I started looking at the back of the factory and started running numbers, and decided I’d do it over there and put in retail.” The first retail he secured was Yazoo Brewing Company, and when the American Pickers flagship moved in about seven years ago, it sealed the deal for an influx of even more shops and businesses. At present, Marathon has 25 retail stores, including Jack Daniel’s General Store, Bang Candy Company and Harley Davidson, along with businesses such as Third Coast Comedy Club and Lightning 100 (100.1 FM).

All the while, Barry was fixated on Marathon’s history. His research took him back to his hometown of Jackson, Tennessee, where he was directed to talk to the man who owned the old Southern Engine and Boiler Works building. “I went to talk to Mr. Wallace, who was in his 90s,” Barry says. “I told him, ‘I’d like to see if there’s anything in Southern Engine and Boiler Works on the Marathon car.’ Mr. Wallace said, ‘Son, I’m 92 years old. My dad told me about that car, but I don’t remember anything about it. You’re welcome to go through that building — just don’t fall through the floors. You can have anything you want.'”

Barry did just that, carefully working his way through each floor of the run-down complex in Jackson and documenting with photographs along the way. Knowing that Marathon engineer William Henry Collier had designed steam engines there as a young man, he was optimistic. However, the building had been cleared out years before, leaving nothing behind … or so he thought until he reached the third floor and discovered a walk-in safe. “It had all these dates on it,” Barry tells us, “and all the paint was so old. There was a little step going up to a landing and then it turned and went up toward the roof, and there was a little closet that went back about two feet. I thought, ‘That’s weird.’ The closet had a trim around it. So, I’m moving spiderwebs and taking pictures, and I see a really thin crack in the shape of a door.” Beating off the ancient layers of plaster revealed more than Barry could have hoped for — the stuff legends are made of. “I pried it open, and it was a sealed-off dark room. William Collier, Marathon, Southern Engine and Boil Works … it was like a tomb. And that’s all the stuff out in the hallway at my office.” He adds, “Now, you’ve got to remember, I just happened to come by here, to this old abandoned building in Nashville, Tennessee, and it leads me back to my hometown, where I find a sealed off dark room. And this story is just getting started. ”

Barry likes to say his personal story is kind of like Forrest Gump, only it’s true — nothing fabricated or exaggerated. After his discovery in Jackson, he got deeper into his research on William Collier and “bringing him back to life.” This quest led him to several other discoveries that seem more fated than coincidental. In one case, knowing he was a history buff and didn’t mind getting his hands dirty, Barry was called upon to sift through heaps of paper trash in an old house the city of Nashville intended to tear down. He went in to assess the wreckage, only to find three feet of paper on every floor of the house — hoarded stacks of newspapers and various other documents. In fact, it was piled so high that they uncovered a piano, worth about $15,000. So, Barry began the treacherous task of sifting through. He started at the top, which were papers from the 1960s and ’70s, and as he continued to work through the stacks, he stumbled across pre-Civil War letters. The deeper he dug the more he found, so he began trying to pinpoint anything written prior to 1925. He loaded up about 150 boxes worth of paperwork and methodically went through each one. Finally, when he got down to 1918 or 1919, he started coming across leases — that’s when he realized the homeowner’s grandfather must have owned half of Nashville, with properties from one side of the city to the other. Barry had a funny little inkling, even saying to a friend, “Wouldn’t it be funny if he owned a house and leased to William Collier way back when?” And lo’ and behold, one day he found it — his needle in a haystack — a lease signed by William Collier himself. “What are the odds of me finding that paper in the millions of hoarded papers over three stories?” Barry asks. “I didn’t even know it was in there when I started looking. I was just going through because I love old letterheads.”

One thing is clear: Barry Walker was meant to tell the story of Marathon Motor Works. In fact, we can also credit him with saving it, since all of the buildings were slated to be torn down, and Marathon’s history would have been lost along with them.

In a matter of speaking, the modern-day Marathon buildings also tell the stories of other Nashville legacies. A master recycler, Barry explains all of the glass in his office came from the former Red Cross building; the spiral staircase came from the Tennessee Theatre. He points out exterior stairs that he purchased for $150 from the Cool Springs Mall, as well as windows from the original Hatch Show Print, which he extracted with the help of sculptor Alan LeQuire. In the upstairs hall of the Marathon factory, there’s even a sculpture made from a big truck chassis that was dug up when the football stadium was built — right around the 30-yard line. “I’ve got stuff from everywhere that’s been torn down in this city,” he says. “I go to the dumpsters and get stuff — warehouses, hotels, auctions, you name it.” He has also spent years collecting vintage car parts and machinery, turning them into an industrial museum that is viewable throughout the factory. He says it’s his dedication to quality of life. “Back at the turn of the century, everybody respected people,” he says. “That shows even in the machinery — they even had beautiful details in machines. From the shape of the metal to the pinstriping, we built quality machines.”

Of his museum efforts, Barry says, “Young people need to know where we came from. You’ve got to know where you came from before you go forward. The industrial museum I’ve designed and built, it shows how they built cars 100 years ago, but it also shows the quality of them.”

The progress at Marathon is ongoing. Barry is currently building a combination museum and bar he has been designing for 20 years, called Gear Heads, based on pre-1918 racing. He has also added the Collier house and factory in Jackson to his Marathon roster. When we ask what his favorite piece might be, the historic storyteller briefly mentions wrecks he recovered while black water diving. But his hands-down favorite is the Marathon building itself. “I get to bring the puzzles of these people’s lives back out after 100 years,” he says. And it doesn’t stop there. Barry is preserving his personal history as well, recycling his own tools, and turning them into functional art. In fact, the front of the door of the administrative building is the first saw blade Barry ever bought. He has it welded to the door.

After 30 years of devoting his life to Marathon Village, Barry has taken on a super-secret new project on the Cumberland River here in Nashville. It took him 30 years to acquire it, but as with everything else he has accomplished, he never gave up. Discovered while he was on a black water diving trip, his newest passion project is renovating the old pumping station for Nashville Railway and Light — a company started by Percy Warner. Given Barry’s impact on Marathon Motor Works, we have no doubt the pumping station is in for a stunning rebirth … and Barry is in for another adventure.

**********

For your daily dose of StyleBlueprint sent straight to your inbox every morning, click HERE!