I remember December 14, 2012, like it was yesterday, hearing the news about how Adam Lanza entered Sandy Hook Elementary School and murdered 20 school children and six staff members. That was after he shot and killed his mother, but before he shot and killed himself. That day, as I drove to pick up my children, then in sixth, fourth and second grades, I couldn’t stop crying as I listened to the news on the radio, each emerging detail worse than the one before it.

I sat in the carline, and I remember thinking that my husband and I needed to tell the kids what happened, to explain this horrific event to their young and impressionable minds before they heard it anywhere else. So that evening, we told them what had happened in Newtown, CT, earlier that day. We were discreet but honest, trying to be truthful but not terrifying. For a moment, it was like crickets chirping. And then came the flood of questions and comments, each one valid but heartbreaking. One of my kids struggled more than the others, sensitive by nature and very much a “feelings-driven” child. He couldn’t fall asleep on his own that night, so we allowed him to climb into our bed for comfort. And the remaining days before Christmas break were challenging as he was afraid to be apart from us, afraid of what could happen to him at school.

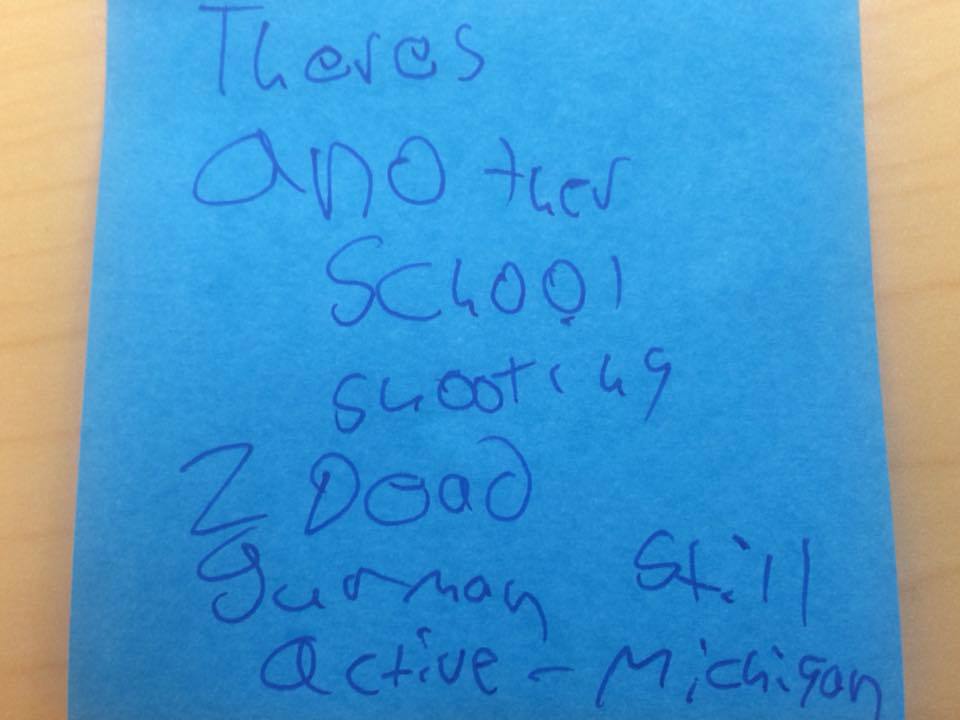

My boys are now in 11th, ninth and seventh grades, and all three are what I consider to be well-adjusted, average, run-of-the-mill kids. They have phones and friends, and the older two dabble in social media, though not obsessively. They are growing up and appropriately detaching from their parents, a process I’m told is normal … a sign that they’re preparing for life outside of the nest. As such, when the Parkland school shooting happened on Valentine’s Day, my husband and I weren’t the ones sharing what had happened with them. My kids learned about the event — and all of the available details — on their own, by way of social media and news and friends. They saw the videos that the students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School took while they were on lock down inside the school, chilling proof of just how terrifying it all was, though surely not doing justice to the in-person experience. They learned how the shooter pulled the fire alarm to get the students to come out of their classrooms before he opened fire, and how the students called and texted their families to let them know they loved them, just in case.

That night, I was glued to the news, and I cried as I watched the students and parents talk to the news people, trying to explain what happened, trying to make sense of and process all of the madness. My son — the same one who struggled with Sandy Hook — came downstairs and sat down next to me on the couch, closer than normal, and he silently watched as well. I asked him a couple of open-ended questions in hopes he would share his thoughts and feelings so we could discuss them. Thankfully, he did open up, and as the tears rolled down his face, he captured everything — every single emotion I imagine many American school-age kids feel — in one simple statement: “It’s just kind of hard to go to school when you’re thinking this could be the last day I’m alive.”

What do you say to that? What CAN you say?!

I have a good friend who teaches middle school, and she brings an insider’s perspective to the topic that frankly I find terrifying.

She says that despite preparation and drills, she still feels like she and her students are sitting ducks should an armed assailant make his way into their school. “In these horrific situations, it is only LUCK that allows folks to walk away,” she posted on her Facebook page shortly after the Parkland shootings. “LUCK that you weren’t in the entryway. LUCK that you weren’t in Room 27. LUCK that you have a classroom closet that will hold 18 kids. LUCK that you or your child had the flu and were home for the day. LUCK that your gym teacher steps in front of the spray of bullets and literally takes one for the team. America wonders why our kids are anxious and depressed?”

And that they are. Our kids ARE anxious. MY kids are anxious. And yet, they bravely get up and go to school everyday, putting on their game faces, which boldly hide the fear and wisdom that far surpass their years.

*****

I was at work yesterday, and my phone rang. It was my son calling. Odd for the middle of a school day, I thought. I answered thinking he was going to ask me to deliver an assignment he’d left at home or ask if he could hang out with friends after school. Instead, he informed me that the school fire alarm had gone off, and that he, along with the rest of the students, were filing out of the school for what he hoped was a fire drill.

“Okay,” I said, clearly perplexed.

“I just wanted to tell you,” he said, picking up on my confusion. “Just in case.”

Ashley Haugen is a married mother of four children — three boys and a girl — who loves her family like crazy.

WANT TO CONTRIBUTE TO “SOUTHERN VOICES”? READ SUBMISSION GUIDELINES AND SUBMIT YOUR ORIGINAL WORK HERE!