Published: January 16, 2020

On January 17, 1920, the 18th Amendment went into effect prohibiting “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors,” a policy known as Prohibition. Tennessee was early to the Prohibition movement, regulating the sale of alcohol as early as 1877 when the “Four Mile Law” banned sales within four miles of rural schools. The restrictions expanded through the years, including some schools in larger towns in the country regions of Tennessee in 1887, then towns with populations under 2,000 with the Peeler Act of 1899. The Adams Bill raised that population limit to 5,000 citizens in 1903, and by 1907 all but the largest cities in the state were officially dry. Finally, in 1909, a statewide prohibition was passed, making the production of alcohol illegal in Tennessee. However, the possession and transportation of spirits were still allowed until the “Bone-Dry Bill” of 1917.

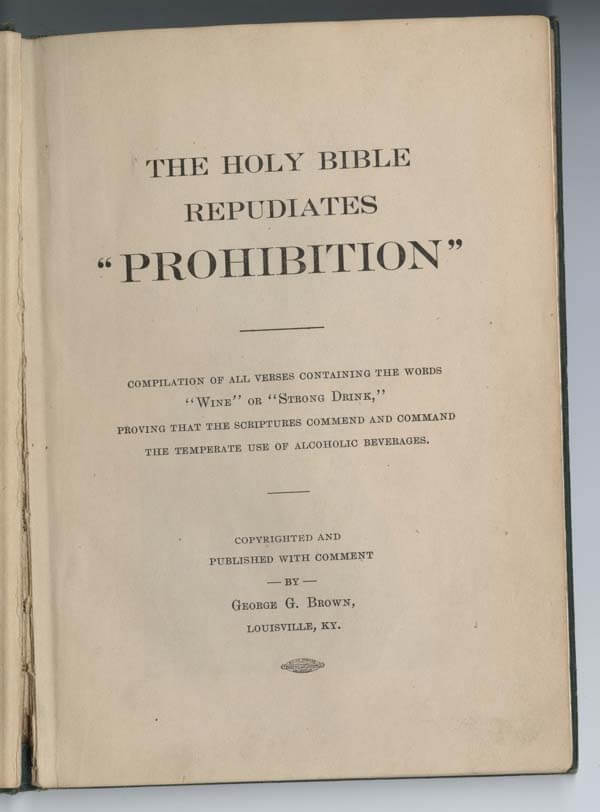

Religious biases against alcohol drove both Tennessee’s 1917 total prohibition and the national Temperance Movement, but they were also wrapped in the patriotism surrounding World War I. The rationale was that the grains used to distill alcohol were needed as food for the troops and the factory employees working to stock up on military equipment and supplies for the war effort. Also, a sober worker was considered a more productive one, so Prohibition was equated with patriotism.

In Tennessee, the timing of state Prohibition was unfortunate for Louisa Nelson, the proprietress of Nelson’s Green Brier Distillery. The spirits company was founded in 1867 and acquired by Louisa’s husband, Charles Nelson, in 1870. Under Charles, the distillery grew into — by far — the largest distillery in the state, reaching its peak around 1885, when they produced 380,000 gallons of whiskey — that’s about 2 million bottles. Charles Nelson passed away in 1891, and Louisa took control of the operations, becoming one of the few women in the industry to run a distillery.

Charles and Louisa’s great-great-great-grandsons, Charlie and Andy Nelson, revived the brand in 2013, and Charlie is well-versed in the family’s history. “Louisa kind of knew Prohibition was coming,” he explains. “While the sales had plateaued, she kept it going strong by diversifying the company’s offerings and really upping the game when it came to marketing.”

While the young Nelsons don’t have all the documentation leading up to Prohibition in their voluminous family and company archives, Charlie has a pretty good idea of what Louisa was going through. “I imagine she was in a really tough spot as a woman running a whiskey company. She was a strong-willed woman who definitely supported women’s suffrage, but many of the same supporters of that movement were the same ones pushing for temperance.” Louisa did demand respect from the community, and Charlie recounts an old family story that he has heard: “Apparently, after Prohibition was enacted, Louisa decided to move from her house on Rutledge Hill to Midtown near Centennial Park, but she had a ton of whiskey and wine to move with her. She had to get a caravan of cars to carry all the booze and a police escort to make the move!”

The law of 1909 prohibited the production of alcohol, but it was still legal to sell to other states that hadn’t yet gone dry. At the time, Louisa Nelson’s distillery had about 8,000 barrels still aging in warehouses, so they shipped them to Kentucky and set up a sales office on Louisville’s legendary “Whiskey Row” along Main Street. She managed to keep the business going through 1915 when they finally sold their last barrel. Charlie and Andy resurrected the family business almost a century later.

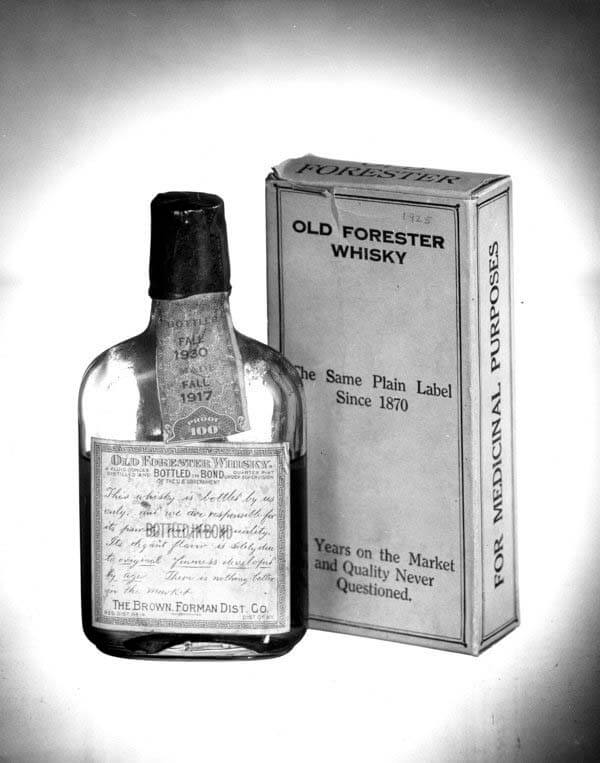

As the national Prohibition efforts began to ramp up around the same time, Kentucky distilleries were also scrambling to prepare themselves for the new reality. One of the oldest and most respected whiskey companies was Old Forester, owned by former pharmaceutical salesman George Garvin Brown, the patriarch of the family that still owns the distillery under the Brown-Forman umbrella. Old Forester was first bottled and marketed in 1870 by George, who named his product after a popular local physician who advocated its purported therapeutic properties.

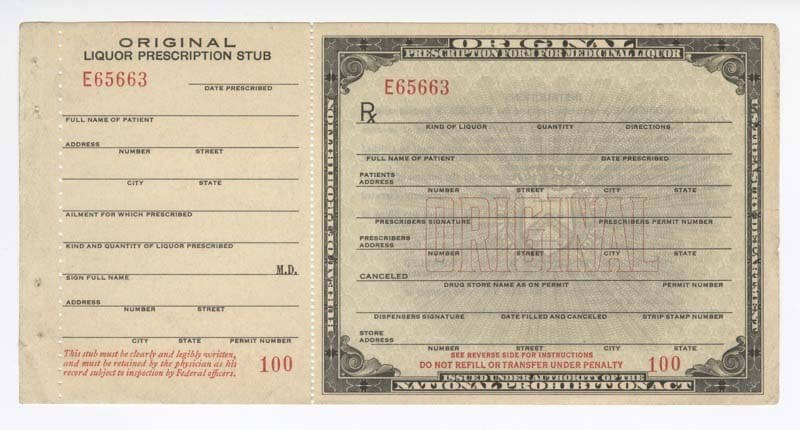

Old Forester was noted as the first whiskey to be sold exclusively in bottles instead of barrels, thus insuring against the possibility of adulteration — a process popular with unscrupulous rectifiers of the age who might add anything to their whiskey to change the color or flavor or to extend their stock of inventory. George’s conscientious procedures probably led to a fortuitous opportunity when the 18th Amendment went into effect on January 17, 1920. A loophole in the law allowed for a limited number of companies to continue to sell alcohol for “medicinal purposes.” While they couldn’t distill new spirits, the six medicinal license holders could bottle their own aging inventory and whiskey from other distilleries in generic pint bottles, which could be purchased by anyone with a doctor’s prescription. It was amazing how many people came down with “a case of the nerves” in the early 1920s.

Chris Morris, Brown-Forman master distiller and an invaluable repository of whiskey history describes the process: “Going through the archives at Brown-Forman, I’ve never discovered exactly what the procedure was to receive a medicinal license, but it seems to have been based on the company’s reputation and bona fides.” Eventually, six Kentucky companies were licensed to sell whiskey during prohibition: Brown-Forman’s Old Forester brand, Frankfort Distilleries (now Four Roses), American Medicinal Spirits (part of Jim Beam now), and three other distilleries that are now under the Diageo umbrella, A. Ph. Stitzel, Schenley and Glenore.

“At the time of Prohibition, there were 210 distilleries in Kentucky, and millions of barrels in warehouses all over the state,” explains Chris. “Most of the distilleries couldn’t sell to consumers, but they could sell them to the six permit holders. The sellers could ask to use their own names on the labels, like Blue Bonnet and Yellowstone, or just sell them to Brown-Forman to release under Old Forester, with the name of the original distiller marked on the label. A lot of whiskey was also sent to Canada and Europe, but it couldn’t come back.”

While this arrangement kept Brown-Forman and the others in business, it certainly was a step backward for the whiskey boom. “George Garvin Brown’s son, Owsley, was running the company during Prohibition, and he always said it wasn’t about getting rich during that time. It was about survival. The company didn’t grow, but at least it maintained.”

By the end of the decade, the medicinal stores were running low, so in 1929, the government granted the six licensees the right to distill an additional three million gallons a year to help maintain the supply to meet the needs of all those nervous patients. While this barely kept up with demand, it did mean that the six permit holders had a head start with four years’ worth of aging whiskey in their warehouses when Prohibition was eventually repealed by the 21st Amendment in 1933.

The ’20s started with a lament named “How Dry I Am” in honor of Prohibition and ended with the much jollier “Happy Days Are Here Again” as one of the most popular songs of the era, which also served as FDR’s campaign theme song. The emergence from the great dry spell had some interesting consequences.

Chris explains one unexpected societal change: “Prohibition actually led to women drinking in bars for the first time. Before Prohibition, bars were considered the domain of men — rough places where women didn’t want to go. In the speakeasy culture that emerged during Prohibition, everyone was welcome in the secret bars, so it became cool for women to be seen there.”

Because the six distilleries with medicinal permits maintained their operations in Kentucky during Prohibition, the Bluegrass State cemented its prominence in the world of whiskey. “The industry reopened with a bang,” notes Chris. “From the six distilleries still operating in 1933, the number in Kentucky had grown to 70 by 1938. Tennessee had only one at that time, Jack Daniel’s.” During the decade of Tennessee Prohibition, before the law went nationwide, almost all of the nearly 1,000 registered distilleries in the state (including many small farm-based operations) shuttered for good. Others moved operations out of state: George Dickel to Louisville and Jack Daniel’s to Hopkinsville, KY, and then to St. Louis.

The main reason Tennessee embraced temperance more staunchly than Kentucky was cultural. Chris explains, “The two states were quite different places. The centers of distilling have historically been in Northern Kentucky near the Ohio River, and Central Kentucky around Louisville and Owensboro. Unlike other regions of the South, these were highly Catholic areas, populated by German immigrants from around Cincinnati, and Maryland Catholics who were pioneers in the area during the late 18th century. These populations didn’t have the same religious bias against alcoholic products that Protestants did. This critical difference cemented Kentucky as the cradle of whiskey going forward.”

Both Nelson’s Green Brier and Old Forester remain whiskey brands steeped in history. The Nelsons recently released their first Tennessee whiskey using one of their great-great-great-grandfather’s original recipes. The recipe of this sour mash whiskey contains wheat, an uncommon grain for Tennessee whiskeys, but a favorite of Charles. Charlie and Andy pieced together the details by researching archives and news stories of the day, and the product has already proven to be quite popular among whiskey aficionados.

Chris also created a new recipe as part of Old Forester’s “Whiskey Row” series of products, special expressions of the bourbon that are referential and reverential of the brand’s long history. Old Forester 1920 Prohibition Style Whisky (spelled without the “e” in historical style) is bottled at a higher proof level than regular Old Forester. “Owsley Brown took over the business in 1917,” explains Chris. “Our traditional barrel entry proof was 100, but we gained alcohol content during aging. I wanted to create a whiskey that would be like what Owsley would have been tasting in the barrels, so we went with 115 proof.” The result is a truly remarkable bourbon that is much sought after by the legions of Old Forester fans.

Chris is proud of his company’s legacy: “Brown-Forman and Old Forester turn 150 this year, making it the oldest continuously produced brand in the U.S. Old Forester is still growing at double digits year-over-year, and it’s unusual for legacy brands to grow like that. There aren’t many pre-Prohibition brand labels left in the marketplace, and the company is still run by a member of the Brown family, Campbell Brown, who serves as president of Old Forester and is a member of the Brown-Forman board of directors. Not many family businesses make it 150 years!”

Charlie Nelson feels lucky to be able to sustain his family legacy that was interrupted by the 18th Amendment. “History and family are really important to us,” he offers. Louisa passed away in 1918 during the middle of Tennessee Prohibition, so she wasn’t able to reopen the company after the ban was lifted. Charlie continues, “It’s kind of like having the football season suddenly end while your team is in first place. Then when the season starts up again, your team has been dissolved. I’m almost glad I didn’t know about it fully when I was growing up. Then, when Andy and I learned the stories about our family business, we knew it was our destiny to start it up again. I’ve always said that whiskey was in my blood, but I didn’t really know why.” When it comes to Old Forester and Nelson’s Green Brier, the history of Prohibition in Tennessee and Kentucky really are family stories.

**********

Subscribe to StyleBlueprint for your best “me moment” of the day. Click HERE.